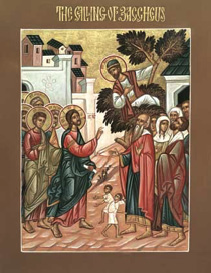

Sunday of Zaccheus

In our Byzantine Tradition, we have a liturgical year—a calendar of liturgies (public worship) formulated centuries ago in order to guide and support us, as Christians, in knowing Christ and living our lives according to His example. Ukrainian folk culture has evolved in accordance with the liturgical year. If we look at the cycle of events in our liturgies, and the customs surrounding them that Ukrainians have practiced we’ll recognize seasons that reflect a universal experience of being human—in the natural world, and in society.

In the Christmas cycle, we’ve encountered the mystery of birth, the wonder of God’s incarnation, and the meaning that Divine embodiment can have on my own understanding of my humanity—what it means to be human. We are still in the Christmas season, singing carols, awaiting Jordan visitations, but as this sequence of Feasts wanes, the liturgies point towards the next wondrous phase of the church year. Having contemplated the divine nature of our humanness, having celebrated light in the dark of winter, we are led now through a period of reflection on how to live our humanity as Christians. For 5 Sundays we hear Gospel narratives that focus on our relationships with each other—to prepare us for the time of Lent when our attention turns from finding God in Others to finding God in ourselves.

This Sunday of Zacchaeus marks a turn from our observance of mortal life—through Great Lent—to Pascha, when together we contemplate the miracle of immortal life.

This Sunday of Zacchaeus marks a turn from our observance of mortal life—through Great Lent—to Pascha, when together we contemplate the miracle of immortal life.

Each year we hear the story of Zacchaeus from Luke 19: 1-10, the same story repeated, just as every other biblical reading returns every year, for over a thousand years. Why? Because the stories can speak to us as human beings in a fresh way each time we hear them. They apply to our individual context and personality (if we let them). They can give us the courage to be as radical in our relationships as Christ was with those He met.

Remember Zacchaeus? He was the despised tax collector: corrupt, traitorous, rich, unscrupulous, and (as if that weren’t enough) short. No one was going to give Zacchaeus a front seat for the parade, so, he climbed a tree to get a glimpse of the miracle working rabbi that was coming to town. Jesus looks up, sees the man and invites himself over to Zacchaeus’s house for supper.

This we know is a lovely reminder to us all that anyone can change their bad ways and accept Christ into their lives. Zacchaeus, like Dickens’s Scrooge, becomes a beacon to his community, better than he could ever have dreamed of being before his encounter with Jesus, with Love incarnate.

We can also learn from the reaction of the crowd, who apparently considered themselves followers of Jesus: good, pious, honest, law-abiding people—definitely NOT tax-collectors. They might have rejoiced at Zacchaeus’s good fortune and conversion. But they didn’t. They resented the attention a sinner received. They were self-righteous. An obvious lesson perhaps, but one that might resonate currently in a particular way when we hear grumbling about the services granted to Syrian refugees. I hate to admit it, but too often I catch myself being envious when someone gets what seems to me to be a “free ride” for something I’ve worked really hard at. Thanks to this Sunday’s reminder, I can give my head a shake, as it were, and be happy. Thank God.

Sunday of the Publican and Pharisee

This Sunday marks the second week of preparation for Lent with the parable of the Publican and the Pharisee.

The story is familiar—heard this time every year—yet each time we hear it, we have an opportunity to see our selves through a new light. How can this be? This is the power of parables. Parables (like fables) allegorically represent a moral lesson. They present a short simple clear event, easy to visualize and remember. But behind the literal story lies the depth of human experience. The fictional characters symbolize human relationships in the presence of God; they teach us, through Christ, how we are to act as members of the Kingdom of heaven. Thus, a parable has the power to speak to every individual’s personal experience every time afresh.

In case the lesson of Zacchaeus last Sunday, (where followers of Jesus grumbled at His choice of dining with a tax-collector), was too subtle, this Sunday gives us another chance to focus on our self-righteousness.

In this story, the figures behave in an opposite way to expectations. The Pharisee is supposed to be the good guy, but he is arrogant, self-obsessed, self-righteous, judgemental; whereas the Publican, who should be the bad-guy, is in fact the model for us: humble, contrite, sincere in his prayer—which in the East becomes the prayer of our breath—“Lord, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

The meaning of this parable for me in my life today may be different than the impact it has on you at this particular time. As we reflect, we detect ever greater significance and relevance.

Both Pharisee and Publican are stereotypes (think hypocritical politician/honourable thief). How often do we judge individuals according to surface: status, skin colour, ethnicity, etc.? Might we trust the elegant woman in the expensive suit but grip our wallet tightly as we walk by the homeless person huddled at the entrance to Sobeys? How often do we judge (self-righteously) without realizing it?

While we might want to relate to the Publican, repentance may not be easy to do. Living a Christian commitment needs constant self-vigilance. The love for others that Jesus exemplified is as radical as it is beautiful.

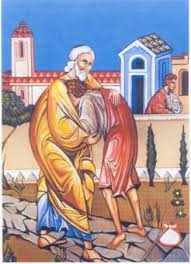

Sunday of the Prodigal Son

Kontakion (Tone 3)

I have recklessly forgotten Your glory, O Father;

And among sinners I have scattered the riches which You had given me. . .

The Fathers of the Church chose the parables of these Sundays before Lent to help us to continue our resolve to live truly as Christians. The stories of Zacchaeus, the Pharisee, and today, the Prodigal Son, demonstrate how enduring (and just ordinary) the struggles are that we face, daily, when we consciously try to live in a way that’s like Christ. These parables not only suggest that the fundamental urge to be selfish and envious of the next guy is a common human trait, but also, that it is just as human to be able to overcome it within ourselves. We have a choice. And, we have to make this choice over and over again.

The Prodigal Son is among the most famous of parables. Perhaps it’s because it illuminates such astonishing generosity. Surely the father’s tender embrace of his disloyal son foreshadows the crucified Christ’s forgiveness of his killers?

This story is positioned to inspire us with hope and comfort as we approach the Lenten focus on repentance. The meaning is familiar and applies to each one of us: no matter how much we’ve messed up, as it were, we will be welcome, when we find our way back home. Yes!

But do we relate to the young man who squandered his inheritance? How many of us even have an inheritance nowadays? Ok, we know that the prodigal’s extreme despair, hunger, self-loathing, emptiness, represents anyone of us—me, you—when we turn away from God. Coming to God means nothing other than love, peace, and joyfulness: home. Chances are, if you are reading this, you are part of the Church community, possibly not contemplating a getaway to a life of iniquity! Probably doing your best to live as a decent citizen.

Significantly, today’s parable also portrays the older brother: loyal, hard-working, supporting the family business; no wine, women, and song for him! It’s not too difficult to imagine why he was less than thrilled at the royal treatment his brother received. He was resentful, bitter, hurt. Not only is he feeling second-best, but he’s expected to cheer on his little brother who had given the family so much grief.

This is a tall order—but one, we are told, we can fill. We CAN rejoice for another. We can practice a selflessness that connects us in love to share another person’s good fortune. The older brother is invited to celebrate: to come home. Despite his physical presence working on the farm, living with the father, the older son too was close to squandering his share of the inheritance. Like the Pharisee, and the crowds surrounding Zacchaeus, this son did the right things, but without the love that takes us beyond our own self-interest into a connection with others where we can delight in each other’s good fortune.

Each figure in today’s parable can enrich our being. We know God through each other, so let’s strive to recognize the goodness around us and be grateful (as children), and like the father, make each other feel at home with us: acknowledged, celebrated, where no one can feel condemned for their shortcomings or unappreciated for their presence. When we can feel that we belong together, we can feel the warmth of God’s welcoming embrace, and our joy multiplies!

Meatfare Sunday or Sunday of the Last Judgement

This is the last day of eating meat, traditionally, until Pascha. One week away from Great Lent, we hear the parable of the Last Judgement, the sheep separated from the goats—goodness rewarded and sin punished.

Then the righteous will answer Him, ‘Lord, when did we see Thee hungry and feed Thee, or thirsty and give Thee drink? And when did we see Thee a stranger and welcome Thee, or naked and clothe Thee? And when did we see Thee sick or in prison and visit Thee?

Then the righteous will answer Him, ‘Lord, when did we see Thee hungry and feed Thee, or thirsty and give Thee drink? And when did we see Thee a stranger and welcome Thee, or naked and clothe Thee? And when did we see Thee sick or in prison and visit Thee?

And the King will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me.’

The previous pre-lenten readings have been leading to this image of the final exam time, as it were, when the teaching, reminders, and mentoring end, and our performance is evaluated. What is the metric for a passing grade? This Sunday’s story tells us plainly that the one criterion by which Christ will judge us is love; love for our neighbour is love of God. Sin is the absence of love. Do we live in love or not? Your (my) humanity develops and thrives only because you have been and continue to be loved. Cruelty, criminality, hunger, and want emerge from a lack of love; caring for others, is how we manifest the Kingdom of Heaven here on earth. This parable tells us that Christ is present not only in our fellow parishioners, family, or friends—He is in every human being, even those most in need. Let’s reach out to Him at every opportunity and, like the father of the prodigal last week, let’s celebrate being home.

Cheesefare/Forgiveness Sunday

This is the final Sunday preparing us for the period of Great Lent: tomorrow begins what are to be the most intense weeks of the year dedicated to reflection, penance, and reconciliation.

I imagine it as if we’ve been checked by a Lifeguard as we stand on a cliff’s edge, about to plunge into the deep sea waters below: goggles?, nose plug?, lifejacket?; repeat swimming directives one more time . . . (check, check, check, . . . )

As we are about to plunge into Lent, the lessons of the prior weeks reappear today in fresh forms, ensuring that we are equipped with all the safety features available to keep us from drowning.

This Sunday’s Gospel reminds us that we have fallen out with God—as Adam and Eve had in the Garden. Sinfulness obscures our knowledge of God. But our contemplation of our shortcomings, troubles, sorrow, is imbued with the hope and joy of the Resurrection.

Hence, this Sunday of the Expulsion from Paradise, is also known as Forgiveness Sunday. Last Sunday’s parable told us that our interaction with others, even the most destitute, are interactions with Christ. Today we are reminded that God’s forgiveness is manifest in our forgiveness of each other. Forgiveness, truly forgiving one another is a powerful force against isolation, division, opposition, hatred—in short, the wages of sin. In the words of A. Schmemman: “To forgive is to put between me and my “enemy” the radiant forgiveness of God Himself.”

How fitting that this Sunday of Forgiveness after today’s Liturgy we’ll also take part in the Vesper Rite of Forgiveness, asking each other for pardon. We enter into Lent as a community united in our commitment to be Christ in our world, our society, our everyday lives in K-W. Most often, Great Lent is associated with fasting. This Sunday is called “Cheesefare” because traditionally this would be the last day for eating any dairy products until Easter Sunday. Last Sunday, “Meatfare” marked the day to stop meat and eggs. The practice of abstinence from foods is intended to help us refocus our attention to our relationship with God. Stepping outside of our comfort zone with something as normal (and essential) as our eating habits is one way of changing our perspective towards our way of being.

However, significantly, the readings from our pre-lenten Sundays repeatedly tell us that we are not to flaunt our fasting, make others uncomfortable with it, nor judge the practice of others. Fasting in our Faith Tradition is not a goal in itself. Fasting has only one goal: to help us focus on Christ so that we reflect His Spirit. As Paul told the Galatians, “the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control” (5: 22-23). If fasting doesn’t help us be better people, it has no virtue in itself.

These lessons from the pre-lenten Sunday Liturgies are fundamental to our very existence as humans beings—as people with a desire to live with meaning and purpose. I cannot imagine a human interaction, be it at home or work, school, or in a crowd, that isn’t informed by the parables of this period: essentially, let’s live in love. On what will we base every action, decision, choice, as we move through each day? Will we care for how we look to others? Or will we care about others?